Today we celebrate the feast of St. Thomas Aquinas, and I want to share this brief biography I first saw posted by Elizabeth Scalia on Facebook. (Do read her excellent Patheos blog, The Anchoress. Her writing is excellent, and her commentary is always thought provoking!)

[hr color=”dark-gray” width=”100%” border_width=”2px” ]

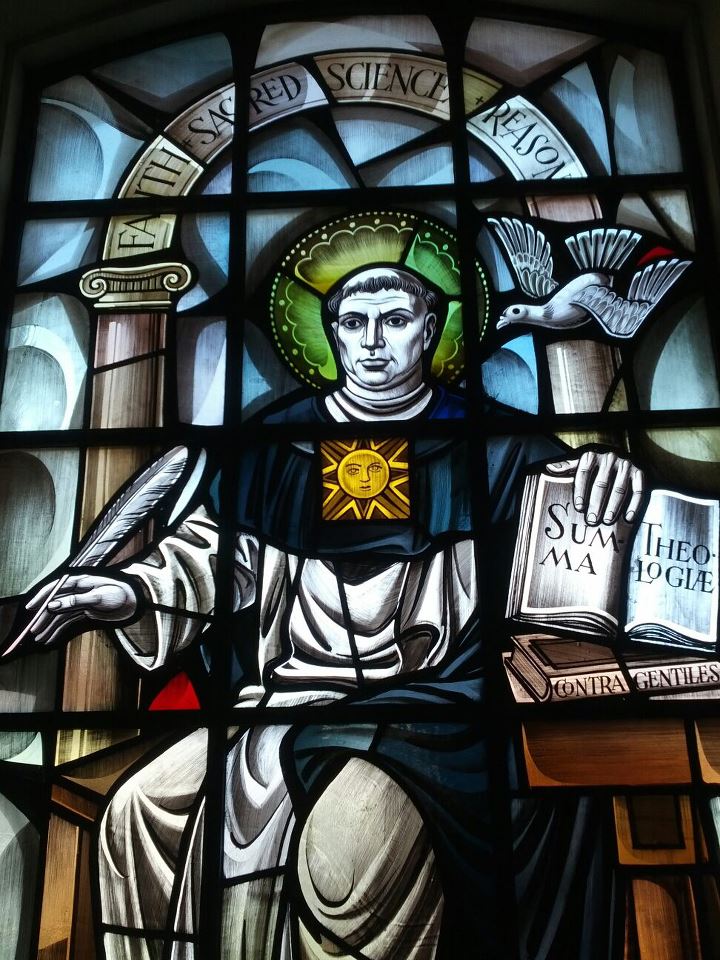

Happy Feast of St. Thomas Aquinas! You think the great scholar led an uninteresting life? Think again. The beginning of his life is like something out of an adventure novel, and includes a furious parent, an abduction, an his chasing a prostitute out of his room with a red-hot poker. Here is an excerpt from “My Life with the Saints.” (Image from St. Paul’s College, Washington, DC.)

. . . . .

Pious legend has it that Friar Tommaso, of the town of Aquino, was an enormous man, so large that his Dominican brothers found it necessary to cut away a section of the refectory table so that he could reach his food. Most physical representations of Thomas, while striving to be polite, show him to be, at the very least, overweight.

In his touching biography St. Thomas Aquinas, the English writer G.K. Chesterton drew out comparisons between Thomas and another beloved saint, Francis of Assisi. Were we to see the two of them coming over the hill in their friars’ habits, the contrast between the two would seem almost comic. (But what a wonderful conversation they would surely have!) Francis, writes Chesterton, was a “lean and lively little man; thin as a thread and vibrant as a bowstring; and in his motions like an arrow from a bow.” Thomas, on the other hand, he describes as a “huge, heavy bull of a man, fat and slow and quiet, very mild and magnanimous but not very sociable; shy, even apart from the humility of holiness.”

Yet this caricature of Thomas Aquinas may be apocryphal. As my moral theology professor liked to point out, Thomas was an inveterate traveler, crisscrossing Europe–moving between Rome, Naples and Paris. And in his day traveling frequently required one to walk–a difficult task for someone with an excessively large frame. Members of the Dominican order, like Thomas, were also asked to walk rather than, say, ride a horse, as part of their spiritual asceticism.

Thomas Aquinas was always on the move, physically, mentally and spiritually. He is arguably the greatest Catholic philosopher and theologian in history, the greatest of what are called the “scholastic” thinkers and the father of “Thomistic” theology, an attempt to understand God’s universe through human reason and which advanced the fundamental insight that “grace perfects nature.” And Thomas’s life offers a good example of just how that grace works.

Butler’s “Lives of the Saints” states that the counts of Aquino, in Southern Italy, came from a family of “noble lineage.” Thomas’s father, named Landulf, was a knight and his mother, Theodora, was of Norman descent.

The exact date of his birth is uncertain, but most scholars agree that it occurred some time in 1225, in the castle of Roccasecca, near the small town of Aquino. The youngest of four sons, Thomas also had several sisters. (Butler is certain about the number of sons, but seems less interested in the precise number of daughters). One night in the castle, while Thomas slept in the same room, one of his sisters was killed by lightning. Not surprisingly, Thomas was terrified of thunderstorms for the rest of his life and would duck into churches whenever one approached. (As a result, he is the patron saint for those in danger of thunderstorms and those facing a sudden death.)

When Thomas was five, his mother and father sent him to the famous Abbey of Monte Cassino, to live as an “oblate,” or associate member. His parents fostered great hopes for a monastic “career” for their young son. Perhaps they thought he might one day be named abbot of the renowned monastery, advancing the family’s fortunes and honor. The boy was educated at Monte Cassino until the age of 13, when he was sent to the University of Naples. There he first became interested in the writings of Aristotle and one of his commentators, the great Islamic philosopher Averroës of Córdoba. It was also in Naples that he was first attracted to the Dominicans, in whose church he liked to pray.

In time, Thomas decided to join the order. The Dominicans, probably anticipating his parents’ opposition, advised Thomas to wait for a time before entering. At nineteen, he received the Dominican habit.

News of his decision reached the castle of Roccasecca to the dismay of his parents, who were still pinning their hopes on a career with the Benedictines at Monte Cassino. Horrified parents, though, were the lot of many saints. When Aloysius Gonzaga announced his desire to enter the Jesuits, his father, the marquis of Gonzaga, threatened to whip him. Pietro de Bernardone, the wealthy cloth merchant of Assisi, was deeply offended by his son Francis’s rejection of his patrimony. (It didn’t help matters that as a symbol of his renunciation of father’s wealth and his own reliance on God, Francis stripped himself naked before Pietro in the town square and handed back to his father even his clothing.)

For her part, Theodora set out to Naples to persuade Thomas to return home. But before she arrived, the Dominicans spirited him away to a convent in Rome. Theodora gave chase, but her son was already on his way to Bologna, travelling with the master general of the Dominicans.

Thus begins one of the strangest episodes in the lives of the saints. (Which, if you think about it, is really saying something.) Infuriated by her son’s recalcitrance, and no doubt worn out from her long journeys, Theodora sent word to Thomas’s brothers, then in the service of the emperor’s army in nearby Tuscany. Their mission was simple: capture their younger brother.

So one day, as Thomas rested near Siena, his brothers waylaid him. First they attempted to strip him of his habit. When this failed, they took him by force back to the castle at Roccasecca and then to the castle of Monte San Giovanni, two miles away, where he was, in essence, jailed. His only visits would be from his sister, Marotta, or, as Butler’s has it, his “worldly minded sister Marotta.” That is, his not-very-religious sister, who would presumably be less likely to do things like pray with her brother. Thomas passed the time by reading the Bible and studying the theologian Peter Lombard’s anthologies of the early church fathers.

Later, the brothers sent a courtesan (Butler calls her “a woman of bad character”) to seduce Thomas. By this point, they had apparently given up even the possibility that he would become a Benedictine monk. In any event, upon seeing the woman Thomas seized a burning poker from the fire and chased her from his chamber.

In 1245, after two years, his family, worn out by his patience, finally gave up and released him. Thomas immediately returned to the Dominicans, who sent him to study first for a year in Paris, and then to Cologne.

Among the other students in Cologne at the time Thomas Aquinas stood out: he was quiet, humble and heavy. So “stolid,” to borrow Chesterton’s description, that his professors thought him a dunce. His behavior earned him the unfortunate nickname “the Dumb Sicilian Ox.” One day a friendly classmate took pity on the poor young man and offered to explain some difficult classwork. But when they arrived at a difficult passage, Thomas, to the classmate’s surprise, explained it in elegant detail.

Soon afterwards, another student came upon a stray page of Thomas’s notes and passed it along to their teacher Albertus Magnus (later St. Albert the Great). At the close of the next day’s lecture the esteemed professor said, “We call Brother Thomas the dumb ox, but I tell you that he will make his bellowing heard to the furthest places of the earth.” During his studies, sometime before 1252, Thomas was ordained a priest.

Thomas returned to the University of Paris to begin his teaching career. While in Paris, he published his first works on philosophy and theology–mostly commentaries on Scripture and on Peter Lombard. Four years later, Thomas received the equivalent of his doctorate, and began his professional career in earnest. From 1259 through 1268, he worked in Naples, Orvieto, Viterbo and Rome, teaching his fellow Dominicans. At the same time, he was busy writing his Summa Contra Gentiles, his vigorous defense of Christianity.

Even at the time, he was recognized for his brilliance, and his scholarship and teaching were in wide demands. As with many other philosophers in the “scholastic” movement, Thomas recognized that the work of any number of scholars–Christian, Jewish or pagan–could lead him to greater understanding of the world around him and the transcendent mystery of God. The novelty of Thomas’s work was his insight that Aristotle’s writings, which had been suspect in the church, could be useful for Christian theology. This gives rise to the common expression –at least common in my own philosophy classes– that Thomas “baptized Aristotle.”

. . .

In 1266, while in Rome, Thomas began his most influential work, the “Summa Theologica,” or a theological synthesis, whose grand aim was to think systematically about a vast range of theological questions. In this case, “systematic” means that everything is tied together, in a sort of system, where what one says about, say, Scripture, has an effect on questions of morals and the attributes of God, and so on.

The Summa’s presentation of difficult theological topics was revolutionary. Thomas’ simple method was first to pose a straightforward question (“Whether God exists”), raise the inevitable reasonable objections (“It seems that God does not exist, because…”), and finally answer both the original question and the objections in a lucid fashion beginning with his usual “Respondeo…” or “I answer…” (“I answer that God’s existence can be proven in five ways…”)

From 1268 through 1272, Thomas returned to Paris, continuing to work on his Scripture commentaries, and on the “Summa Theologica.” He also spent much of his time preparing for the quodlibetales, a popular question-and-answer period, an academic free-for-all, during which the university students gathered in a large lecture hall to pose to their teachers any theological or philosophical questions of their choosing. Thomas, it was said, employed three busy scribes, who worked simultaneously, furiously writing down his wide-ranging thoughts, which he dictated while pacing back and forth. A thirteenth-century multitasker.

But this most intellectual of men was also deeply devout, and frequently enjoyed intense experiences of mystical prayer. He was also admired for his humility and piety. One of his friends said of him, “His marvelous science was far less due to his genius than to the efficacy of his prayers.” The Rev. Richard McBrien writes in his “Lives of the Saints,” “His entire ministry as teacher and preacher was a matter of giving to others what he had himself contemplated, which was for him the highest of all activities when done out of charity.”

Besides his theological treatises, Thomas is also responsible for some of the most beautiful poetry in the Catholic tradition. Thomas, in G.K. Chesterton’s delightful phrase, “occasionally wrote a hymn like a man taking a holiday.” Some of these, like “Pange lingua” and “Tantum ergo,” are among the most popular in the Latin hymnbook, and give lie to the stereotype of the cold, ascetic scholar.

Despite his renown (King Louis consulted him on important matters of state), his writings drew a certain amount of criticism. In 1270, the bishop of Paris, who was also chancellor of the university, established a commission to examine the works of many commentators on Aristotle, including Thomas. The commission drew up a list of condemnable errors and propositions from his writings, a list that was revised and expanded in 1277, three years after his death.

From 1272 to 1274, Thomas returned to Italy, where he taught Scripture at the University of Naples and began the third part of his Summa. But the ambitious Summa would have to be completed by one of his disciples, for by this time Aquinas was already growing increasingly worn out from his many arduous tasks. Thomas was already ill when he was asked by Pope Gregory X to attend the Council of Lyons.

On his way to the Council, Thomas was apparently riding a donkey (unusual for a Dominican, but he was granted that permission because of his weariness) and, in his weakened condition, or perhaps lost in thought, he struck his head on a low-hanging branch. Initially, he was taken to a public inn, but he pleaded to be taken to a religious community.

On the way his condition worsened, and he was taken to a Cisterian abbey of Fossanova, where he was lodged in the room of the abbot. He rallied for a while, and the admiring monks asked the great man to lecture them. Thomas initially put them off, but when pressed, he spoke to them about the Song of Songs, a text that had been dear to the founder of the Cistercians, Bernard of Clairvaux. But before long he relapsed.

After confessing his sins and receiving the last rites from the abbot, he died, at age 50. That same day, so goes the legend, his great friend Albertus Magnus burst into tears in the presence of his community, and told them that he felt in prayer that Thomas had died.

St. Thomas Aquinas was canonized in 1323, and was declared a Doctor of the Church, that is, an eminent teacher of the faith, in 1567. He is popularly known as the “Angelic Doctor” (because of his long and typically detailed accounts of the angels as purely spiritual substances). In 1879 the papal encyclical Aeterni Patris, commended the theology of St. Thomas to theology students, and heralded a revival of interest in Thomistic theology.

But it was not the philosophy or theology of Thomas that drew me to the saint. That is, it was less his elegant argumentation and more the person of Thomas, and his life. I liked him more for who he was than for what he wrote. Specifically, it was the person I met in G.K. Chesterton’s biography St. Thomas Aquinas whom I found so compelling and attractive. The immensely learned man given to deep humility. The theologian whose lifelong study of God drew him ever closer to God. The famously busy scholar who was not too busy to write a poem or a hymn. The active person whose life was absolutely rooted in prayer.

From “My Life with the Saints”: http://www.amazon.com/My-Life-Saints-James-Martin/dp/0829426442